Digital Signal Processing Basics: Digital Filters

Categories:

8 minute read

Digital Signal Processing (DSP) is essential in modern technology, enabling devices to manipulate signals such as audio, video, and sensor data. A key component of DSP is the use of digital filters, which are algorithms that process digital signals to emphasize certain frequencies and attenuate others. This is crucial for cleaning up signals, improving data quality, and ensuring accurate signal interpretation.

In this blog post, we’ll explore the basics of digital filters, how they work, different types of digital filters, their applications, and key concepts for understanding their role in digital signal processing.

What are Digital Filters?

A digital filter is a mathematical algorithm applied to digital signals to modify their properties in some desirable way. Digital filters are used to remove unwanted parts of a signal, such as noise, or to extract useful parts, such as certain frequencies. They work by manipulating a digital input signal in a systematic manner, providing a modified digital output.

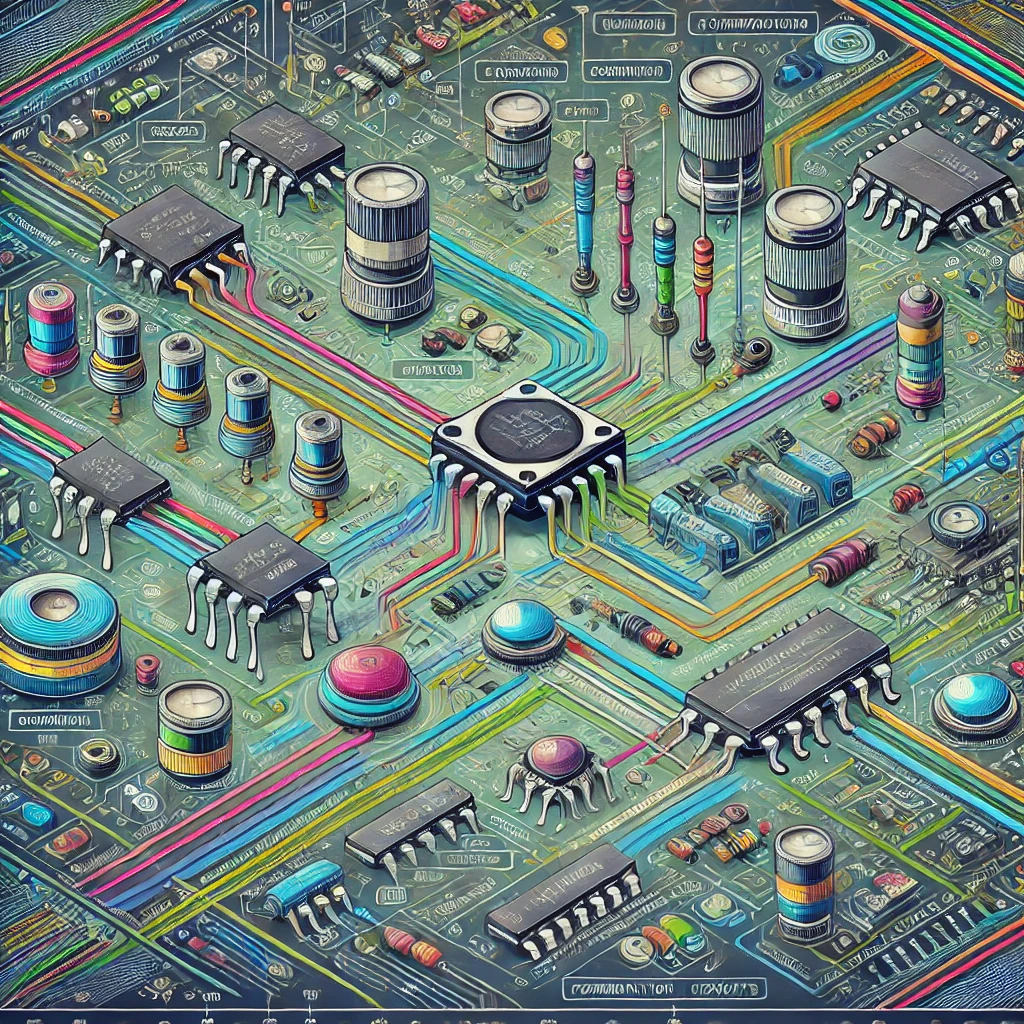

Unlike analog filters, which are implemented using physical components like resistors, capacitors, and inductors, digital filters are implemented in software or hardware using mathematical operations. Digital filters have several advantages, including:

Flexibility: They can be easily reprogrammed or updated.

Accuracy: They offer precise control over filter characteristics.

Stability: Digital filters are less affected by temperature, aging, or environmental factors compared to analog filters. How Digital Filters Work

Digital filters operate on discrete-time signals, which means that the signal is represented by a sequence of numbers, typically sampled from an analog signal. The process of filtering involves convolving this discrete signal with a set of filter coefficients, which define how the filter processes the signal.

A simple example of this is a moving average filter, where each output value is the average of a fixed number of input values. More complex filters use advanced mathematical techniques, including convolution, to achieve specific filtering effects.

The general operation of a digital filter can be described by a difference equation, which relates the current output of the filter to previous inputs and outputs. This equation defines the filter’s behavior and determines how it responds to different frequencies in the input signal.

Key Concepts in Digital Filters

Before diving into the different types of digital filters, it’s important to understand some key concepts that are fundamental to digital filtering:

Frequency Response: This describes how a filter reacts to different frequency components of the input signal. Filters are designed to either pass, block, or attenuate certain frequencies, and the frequency response tells us how the filter behaves across the entire frequency range.

Impulse Response: This is the output of a filter when it is excited by an impulse (a signal with all frequency components). A filter’s impulse response gives insight into its time-domain behavior, and it is especially important in designing and analyzing filters.

Linear Time-Invariant (LTI) Systems: Most digital filters are considered LTI systems, meaning their behavior is linear (output is proportional to input) and time-invariant (the filter’s characteristics don’t change over time). This property simplifies the analysis and design of filters.

Poles and Zeros: These are mathematical terms used in the design and analysis of digital filters. Poles determine the stability and frequency response of the filter, while zeros determine the frequencies that the filter attenuates or blocks.

Causal and Non-Causal Filters: A causal filter processes the current input and past inputs to produce the current output. A non-causal filter processes future inputs as well, but these are typically used only in offline processing where future data is already available. Types of Digital Filters

There are two primary categories of digital filters: Finite Impulse Response (FIR) filters and Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) filters. These two types differ in terms of their structure, complexity, and behavior.

1. Finite Impulse Response (FIR) Filters

FIR filters have an impulse response that lasts for a finite duration. They are defined by a finite set of coefficients that are applied to the input signal to produce the output. FIR filters are typically simpler to design and are always stable, making them a popular choice in many DSP applications.

Key Features of FIR Filters:

Linear Phase Response: FIR filters can be designed to have a linear phase response, meaning they do not introduce phase distortion in the signal. This is important in applications like audio processing, where preserving the waveform shape is critical.

Always Stable: FIR filters are inherently stable because they do not have feedback elements. The output is calculated using only the input signal, not past outputs.

Simple to Implement: FIR filters can be implemented using simple convolution, which makes them computationally efficient for certain applications.

Example of FIR Filter Operation:

The output of an FIR filter can be represented by the following equation:

y[n] = b0 x[n] + b1 x[n-1] +…. + bM x[n-M]

Where:

( y[n] ) is the output at time step ( n )

( x[n] ) is the input at time step ( n )

( b0, b1, .., bM ) are the filter coefficients

( M ) is the order of the filter (the number of previous input values used)

Applications of FIR Filters:

Audio Equalization: FIR filters are commonly used in audio processing to adjust the frequency response of audio signals, allowing for treble, bass, or midrange enhancement.

Image Processing: FIR filters are used to smooth or sharpen images by adjusting the frequency content of the image data.

Signal Averaging: In applications where noise reduction is critical, FIR filters can be used to smooth out high-frequency noise.

2. Infinite Impulse Response (IIR) Filters

IIR filters have an impulse response that theoretically lasts forever, due to the presence of feedback in the filter structure. This means that the current output depends not only on the current and past inputs but also on past outputs.

Key Features of IIR Filters:

Efficient Filtering: IIR filters generally require fewer coefficients than FIR filters to achieve a similar frequency response, making them computationally more efficient for real-time processing.

Non-Linear Phase Response: IIR filters introduce phase distortion, which can be a disadvantage in applications where phase preservation is important.

Potentially Unstable: IIR filters can become unstable if not carefully designed, as the feedback loop can cause the filter to oscillate or produce infinite outputs.

Example of IIR Filter Operation:

The output of an IIR filter is typically represented by a recursive equation:

y[n] = b0x[n] + b1 x[n-1] + … + bMx[n-M] - a1y[n-1] - … - aN y[n-N]

Where:

( y[n] ) is the output at time step ( n )

( x[n] ) is the input at time step ( n )

( b0, b1, .. , bM ) are the feedforward coefficients

( a1, … , aN ) are the feedback coefficients

Applications of IIR Filters:

Telecommunications: IIR filters are widely used in communication systems to filter noise and interference from transmitted signals.

Control Systems: In control systems, IIR filters are used to smooth sensor data and improve the stability of the control loop.

Biomedical Signal Processing: IIR filters are commonly used in medical devices such as ECG monitors to remove noise and enhance the signal of interest. Filter Design Considerations

When designing digital filters, several factors need to be considered to ensure that the filter meets the requirements of the application:

Filter Order: The order of the filter determines the number of coefficients and the complexity of the filter. Higher-order filters can achieve steeper frequency cutoffs, but they also require more computational resources.

Passband and Stopband: The passband refers to the range of frequencies that the filter allows to pass through, while the stopband refers to the range of frequencies that are attenuated. The transition between the passband and stopband is defined by the filter’s cutoff frequency.

Stability: For IIR filters, stability is a critical concern. The poles of the filter must lie within the unit circle in the z-plane to ensure stability.

Phase Distortion: For applications where maintaining the shape of the waveform is important (such as audio processing), FIR filters are preferred due to their linear phase characteristics. Real-World Applications of Digital Filters

Digital filters are integral to many modern technologies. Here are a few examples of how digital filters are used in different industries:

1. Audio Processing

In audio processing systems, digital filters are used to modify sound frequencies. Equalizers in audio equipment use filters to adjust the amplitude of specific frequency bands, allowing users to enhance bass, midrange, or treble tones.

2. Image Processing

In digital image processing, filters are applied to smooth, sharpen, or enhance image features. For example, a low-pass filter might be used to remove noise from an image, while a high-pass filter might be used to enhance edges and details.

3. Communication Systems

In telecommunications, digital filters are used to clean up signals that have been degraded by noise or interference. Filters help ensure that only the desired frequencies are transmitted or received, improving signal quality.

4. Biomedical Signal Processing

In medical devices such as ECG or EEG monitors, digital filters are used

to remove noise and artifacts from physiological signals, allowing for more accurate diagnosis and monitoring.

Conclusion

Digital filters are a cornerstone of digital signal processing, providing a way to manipulate and refine digital signals in countless applications, from audio and image processing to communications and biomedical systems. By understanding the basics of FIR and IIR filters, how they work, and their unique advantages and limitations, engineers and designers can choose the appropriate filter type for their specific needs.

Whether you’re reducing noise, emphasizing certain frequencies, or enhancing data, digital filters are powerful tools that help ensure high-quality signal processing across a variety of industries.

Feedback

Was this page helpful?

Glad to hear it! Please tell us how we can improve.

Sorry to hear that. Please tell us how we can improve.